Portal:History of science

The History of Science Portal

The history of science covers the development of science from ancient times to the present. It encompasses all three major branches of science: natural, social, and formal. Protoscience, early sciences, and natural philosophies such as alchemy and astrology during the Bronze Age, Iron Age, classical antiquity, and the Middle Ages declined during the early modern period after the establishment of formal disciplines of science in the Age of Enlightenment.

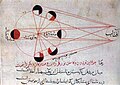

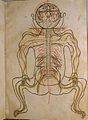

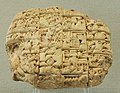

Science's earliest roots can be traced to Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia around 3000 to 1200 BCE. These civilizations' contributions to mathematics, astronomy, and medicine influenced later Greek natural philosophy of classical antiquity, wherein formal attempts were made to provide explanations of events in the physical world based on natural causes. After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, knowledge of Greek conceptions of the world deteriorated in Latin-speaking Western Europe during the early centuries (400 to 1000 CE) of the Middle Ages, but continued to thrive in the Greek-speaking Byzantine Empire. Aided by translations of Greek texts, the Hellenistic worldview was preserved and absorbed into the Arabic-speaking Muslim world during the Islamic Golden Age. The recovery and assimilation of Greek works and Islamic inquiries into Western Europe from the 10th to 13th century revived the learning of natural philosophy in the West. Traditions of early science were also developed in ancient India and separately in ancient China, the Chinese model having influenced Vietnam, Korea and Japan before Western exploration. Among the Pre-Columbian peoples of Mesoamerica, the Zapotec civilization established their first known traditions of astronomy and mathematics for producing calendars, followed by other civilizations such as the Maya.

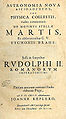

Natural philosophy was transformed during the Scientific Revolution in 16th- to 17th-century Europe, as new ideas and discoveries departed from previous Greek conceptions and traditions. The New Science that emerged was more mechanistic in its worldview, more integrated with mathematics, and more reliable and open as its knowledge was based on a newly defined scientific method. More "revolutions" in subsequent centuries soon followed. The chemical revolution of the 18th century, for instance, introduced new quantitative methods and measurements for chemistry. In the 19th century, new perspectives regarding the conservation of energy, age of Earth, and evolution came into focus. And in the 20th century, new discoveries in genetics and physics laid the foundations for new sub disciplines such as molecular biology and particle physics. Moreover, industrial and military concerns as well as the increasing complexity of new research endeavors ushered in the era of "big science," particularly after World War II. (Full article...)

Selected article -

Evolutionary thought, the recognition that species change over time and the perceived understanding of how such processes work, has roots in antiquity. With the beginnings of modern biological taxonomy in the late 17th century, two opposed ideas influenced Western biological thinking: essentialism, the belief that every species has essential characteristics that are unalterable, a concept which had developed from medieval Aristotelian metaphysics, and that fit well with natural theology; and the development of the new anti-Aristotelian approach to science. Naturalists began to focus on the variability of species; the emergence of palaeontology with the concept of extinction further undermined static views of nature. In the early 19th century prior to Darwinism, Jean-Baptiste Lamarck proposed his theory of the transmutation of species, the first fully formed theory of evolution.

In 1858 Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace published a new evolutionary theory, explained in detail in Darwin's On the Origin of Species (1859). Darwin's theory, originally called descent with modification is known contemporarily as Darwinism or Darwinian theory. Unlike Lamarck, Darwin proposed common descent and a branching tree of life, meaning that two very different species could share a common ancestor. Darwin based his theory on the idea of natural selection: it synthesized a broad range of evidence from animal husbandry, biogeography, geology, morphology, and embryology. Debate over Darwin's work led to the rapid acceptance of the general concept of evolution, but the specific mechanism he proposed, natural selection, was not widely accepted until it was revived by developments in biology that occurred during the 1920s through the 1940s. Before that time most biologists regarded other factors as responsible for evolution. Alternatives to natural selection suggested during "the eclipse of Darwinism" (c. 1880 to 1920) included inheritance of acquired characteristics (neo-Lamarckism), an innate drive for change (orthogenesis), and sudden large mutations (saltationism). Mendelian genetics, a series of 19th-century experiments with pea plant variations rediscovered in 1900, was integrated with natural selection by Ronald Fisher, J. B. S. Haldane, and Sewall Wright during the 1910s to 1930s, and resulted in the founding of the new discipline of population genetics. During the 1930s and 1940s population genetics became integrated with other biological fields, resulting in a widely applicable theory of evolution that encompassed much of biology—the modern synthesis. (Full article...)

Selected image

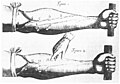

Der Quacksalber (The Quack) is a painting (oil on wood, 53 x 56 cm) by Franz Anton Maulbertsch, from some time before 1785. The subject, of course, is quackery—the peddling of unproven, and sometimes dangerous, medicines, cures or treatments— which has existed throughout the history of medicine. In ancient times, theatrics were sometimes mixed with actual medicine to provide entertainment as much as healing. Quack medicines often had little in the way of active ingredients, or had ingredients which made a person feel good, such as what came to be known as recreational drugs. Morphine and related chemicals were especially common, being legal and unregulated in most places at the time. Arsenic and other poisons were also included.

Did you know

...that the word scientist was coined in 1833 by philosopher and historian of science William Whewell?

...that biogeography has its roots in investigations of the story of Noah's Ark?

...that the idea of the "Scientific Revolution" dates only to 1939, with the work of Alexandre Koyré?

Selected Biography -

Hans Albrecht Bethe (/ˈbɛθə/; German: [ˈhans ˈbeːtə] ⓘ; July 2, 1906 – March 6, 2005) was a German-American physicist who made major contributions to nuclear physics, astrophysics, quantum electrodynamics and solid-state physics, and received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1967 for his work on the theory of stellar nucleosynthesis. For most of his career, Bethe was a professor at Cornell University.

In 1939, Bethe published a paper which established the CNO cycle as the primary energy source for heavier stars in the main sequence classification of stars, which earned him a Nobel Prize in 1967. During World War II, Bethe was head of the Theoretical Division at the secret Los Alamos National Laboratory that developed the first atomic bombs. There he played a key role in calculating the critical mass of the weapons and developing the theory behind the implosion method used in both the Trinity test and the "Fat Man" weapon dropped on Nagasaki in August 1945. (Full article...)

Selected anniversaries

- 1633 - Galileo Galilei arrives in Rome for his trial before the Inquisition

- 1672 - Birth of Étienne François Geoffroy, French chemist (d. 1731)

- 1743 - Birth of Joseph Banks, English botanist and naturalist (d. 1820)

- 1787 - Death of Ruđer Bošković, Croatian scientist and diplomat (b. 1711)

- 1805 - Birth of Peter Gustav Lejeune Dirichlet, German mathematician (d. 1859)

- 1880 - Thomas Edison observes the Edison effect

- 1910 - Birth of William Shockley, American physicist and eugenicist, Nobel Laureate (d. 1989)

- 1956 - Death of Jan Łukasiewicz, Polish mathematician (b. 1878)

- 1960 - Nuclear testing: France tests its first atomic bomb

- 1992 - Death of Nikolay Bogolyubov, Russian mathematician (b. 1909)

- 1997 - Death of Mark Krasnosel'skii, Russian–Ukrainian mathematician (b. 1920)

- 2004 - The Harvard–Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics discovers the universe's largest known diamond, white dwarf star BPM 37093

- 2005 - Death of Emilios T. Harlaftis, Greek astrophysicist (b. 1965)

Related portals

Topics

General images

Subcategories

Things you can do

Help out by participating in the History of Science Wikiproject (which also coordinates the histories of medicine, technology and philosophy of science) or join the discussion.

Associated Wikimedia

The following Wikimedia Foundation sister projects provide more on this subject:

-

Commons

Free media repository -

Wikibooks

Free textbooks and manuals -

Wikidata

Free knowledge base -

Wikinews

Free-content news -

Wikiquote

Collection of quotations -

Wikisource

Free-content library -

Wikiversity

Free learning tools -

Wiktionary

Dictionary and thesaurus